Integers

Integers can be represented in different ways:

Unsigned integer (

uint): range from 0 to $2^n - 1$ for $n$ bits.Signed integer (

int): where the most significant bit is the sign bit (0 for positive and 1 for negative). Range from $-(2^{n-1}-1)$ to $2^{n-1} - 1$. Symmetric range around 0, but it has two zero representations: +0 and -0.Two’s complement representation: A method for representing signed integers where:

- The most significant bit serves as the sign bit (0 for positive, 1 for negative)

- Positive numbers are represented in standard binary

- Negative numbers are obtained by inverting all bits (one’s complement) and adding 1

- Example with 4-bit:

- $5_{10} = 0101_2$

- $-5_{10}$: invert $0101_2 \rightarrow 1010_2$, add 1 $\rightarrow 1011_2$

- Range for n-bit: $[-2^{n-1}, 2^{n-1} - 1]$

- the code 1000…0 represents -2^(n-1)

- only one zero representation: 0000…0 represents 0

- Key advantage: arithmetic operations work uniformly for both positive and negative numbers without special handling

Floating Point

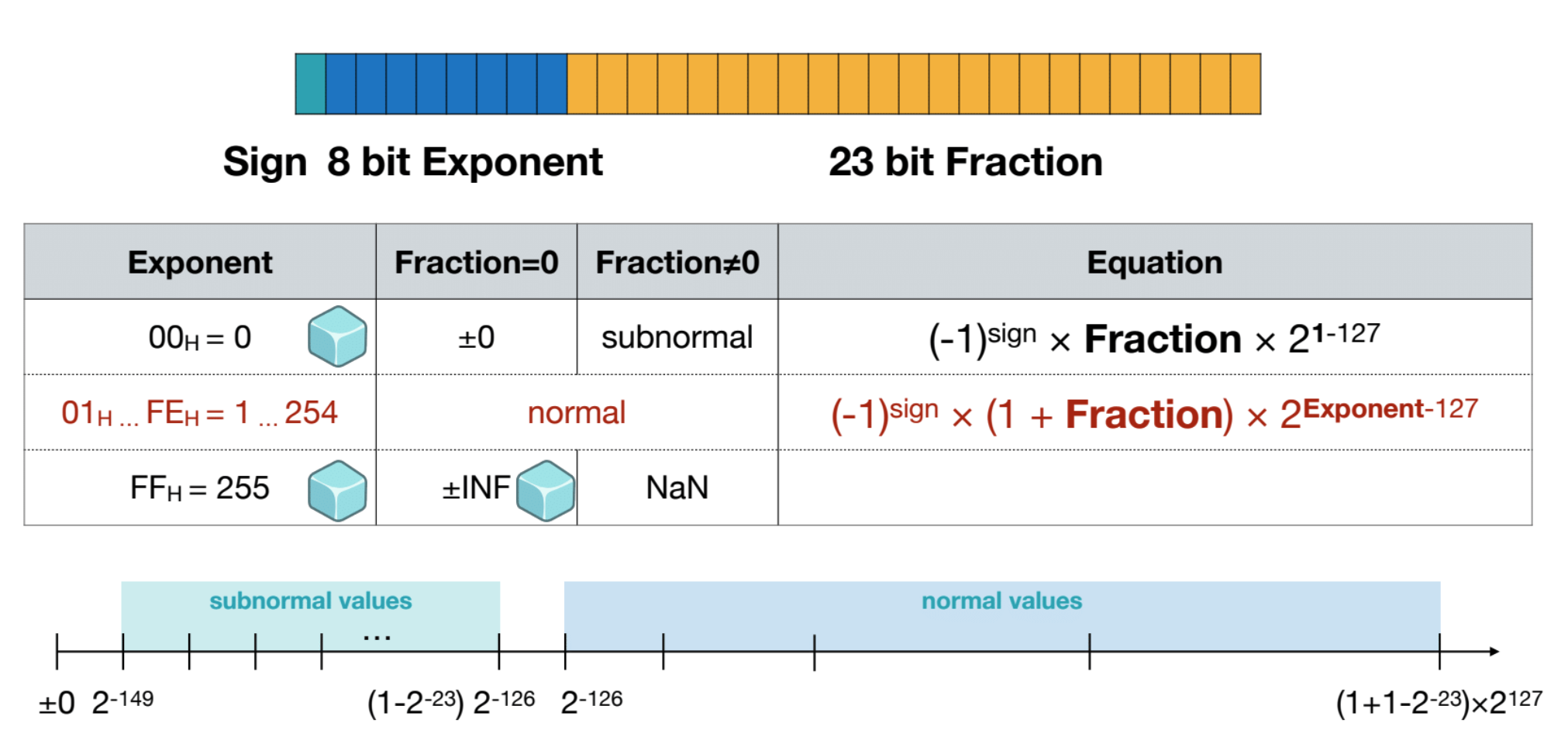

IEEE Floating Point Encoding (ExMy)

- Sign: 1 bit (0: positive, 1: negative)

- Exponent: E bits

- Exponent for a power of 2

- Exponent is biased, so the actual exponent is the stored value minus the bias. Bias = $2^{E-1} - 1$

- Example:

- 5 bits can store values from 0 to 31 (2^5 - 1 = 31)

- Bias = 2^(5-1) - 1 = 15

- Actual exponent = Stored value - Bias

- Special cases: exponent field of all 0s (0) and all 1s (31) are reserved for zeros/subnormals and infinity/NaN respectively

- Largest normal exponent: stored value 30 → actual exponent = 30 - 15 = 15 (represents 2^15)

- Range of normal exponents: 2^(-14) to 2^15. Bias equals the maximum exponent value for normal numbers (15 in this case), which allows for a symmetric range of exponents around zero in the biased representation.

- Mantissa: M bits

- Fractional bits correspond to: $2^{-1}, 2^{-2}, …$

- There is an implied 1 bit before the binary point (unless we’re dealing with subnormals)

FP16 example:

- E5M10: 1 sign, 5 exponent, 10 mantissa bits

- Exponent bias: $2^{5-1} - 1 = 15$

- $0.10001.1010000000_2 = 6.5_{10}$

- $2^{17-15} * \mathbf{1}.101_2 = 2^2 * (1 \text{ (implied } 1 \text{)} + 2^{-1} + 2^{-3}){10} = 4 * 1.625{10} = 6.5_{10}$

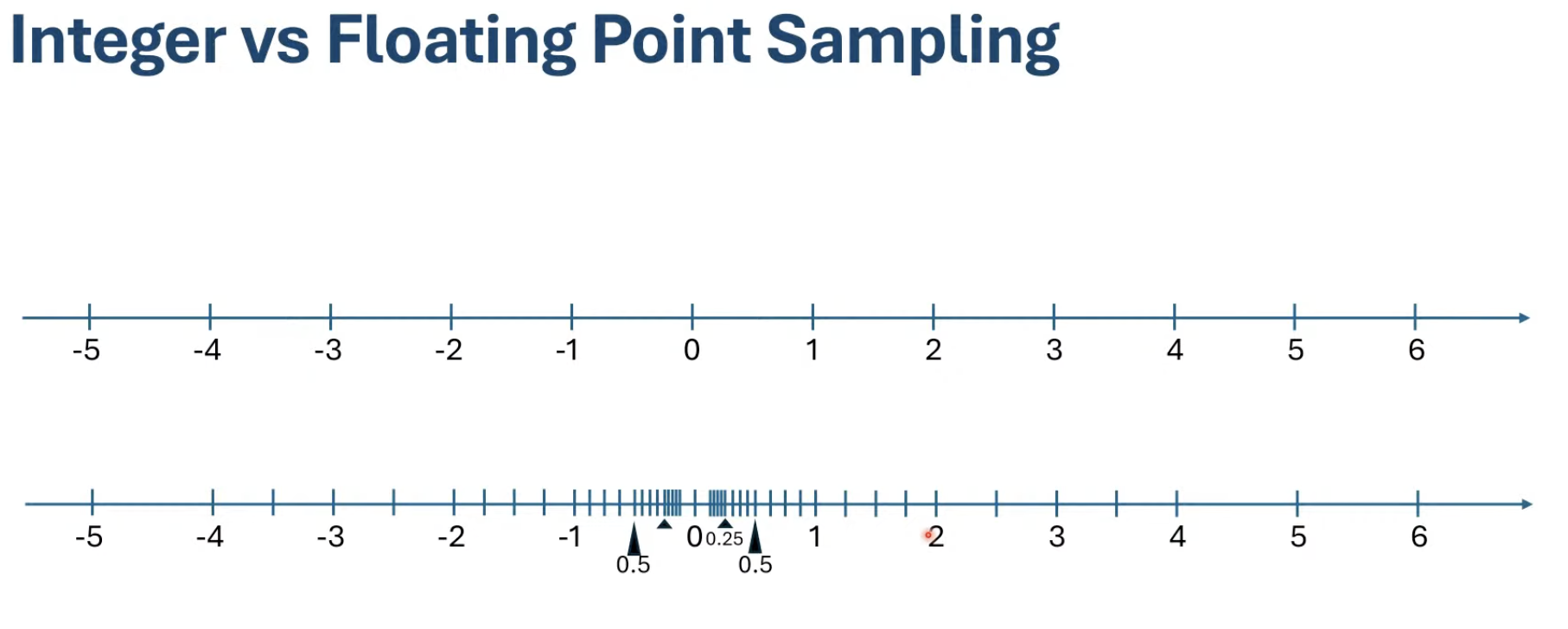

FP Sampling

While integer representation provides equal spacing sampling, floating point representation provides exponential spacing sampling

Exponent bits define which powers of 2 are sampled:

- FP16 (E5M10): exponent samples $2^{-15}$ to $2^{15}$

- Really $2^{-25}$ to $2^{15}$ because of subnormals, more on that later

- Largely determines the dynamic range

Mantissa bits define samples between successive powers of 2:

- E5M10: $2^{10} = 1024$ samples for each power of 2

- Defines the precision

Key observation:

- FP samples the real number line with equal number of samples between each pair of adjacent powers of 2

- Example: E5M10 has 1024 samples between 0.25 and 0.5, between 128 and 256

FP Subnormals

Special interpretation of exponents bits:

- Freeze the exponent bits to all 0s. Thus exponent is $2^0 - bias$ – the min debiased exponent value

- for example, $2^0 - 15 = -14$ for FP16

- Not implied 1 bit in front of the mantissa bits

- $0.00000.1010000000_2 = 2^{-14} * \mathbf{0}.101_2 = 2^{-15} * (1 + 2^{-2})_{10} = …$

- zero is represented as $0.00000.0000000000_2$

Purpose:

- Makes use of the mantissa encodings when exponent is all 0s

- Extends the dynamic range down (but with decreasing precision)

- Extra M powers of 2 can be covered

- More leading mantissa bits set to 0 → lower powers of 2

- This also implies fewer samples for those powers of 2 (fewer remaining mantisa bits)

- $0.000000.1xxxx…: 2^{-15}$ power of 2, 9 bits of precision

- $0.000000.001xx…: 2^{-17}$ power of 2, 7 bits of precision

FP Special Values

There are a number of special values:

- Reserved bit patterns, usually in the exponent field (all 0s or all 1s)

Zeros (positive and negative):

- Exponent and mantissa bits all set to 0

Infinities (2 encodings):

- Positive and negative

- Exponent bits set to 1s, mantissa bits set to 0s

NaNs ($2^{M+1}$ encodings in IEEE):

- Exponent bits set to 1s, mantissa bits contain at least one 1

- Generated by things like sqrt(-1), sum of positive and negative infinity, etc.

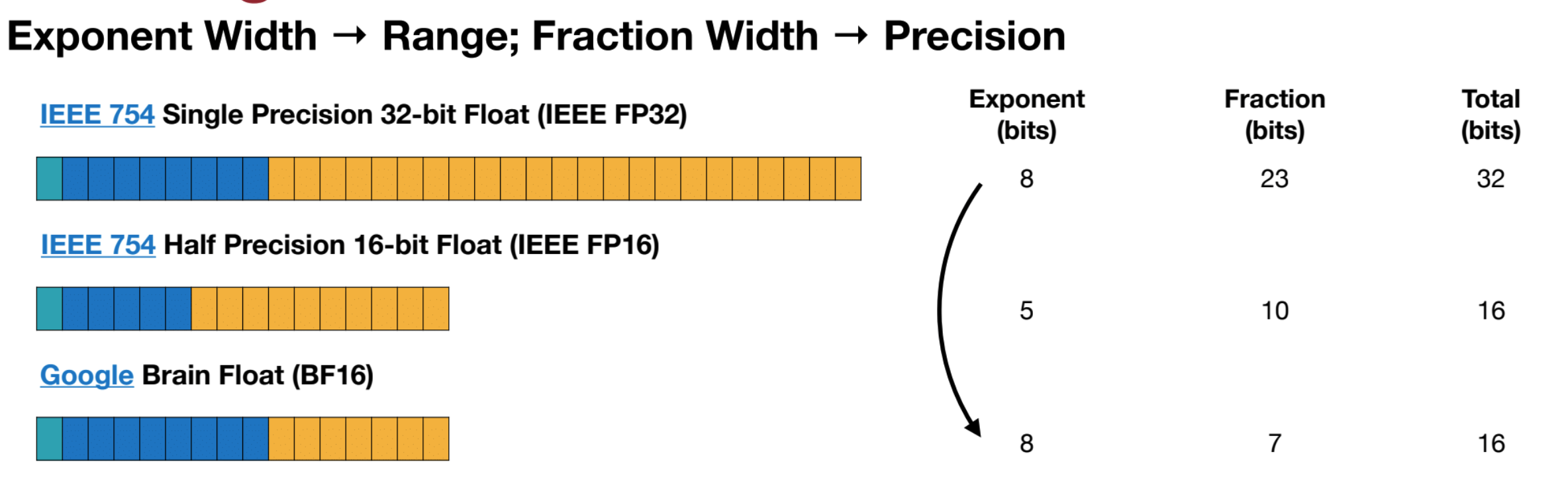

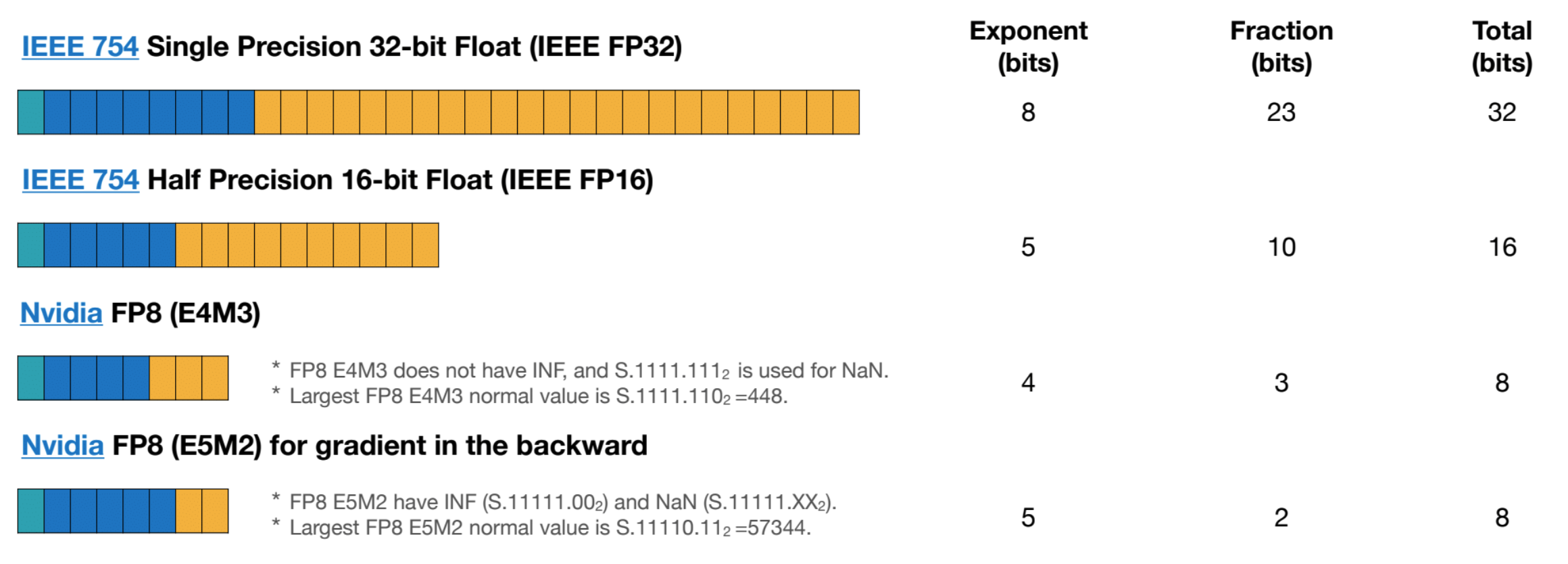

New FP Formats

BF16, FP8, FP4, etc. are invented and used in deep learning, but their standards have not been formalized in IEEE.

BF16 (Brain Float 16):

- 16-bit floating point format

- 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, 7 mantissa bits (E8M7)

- Bias: $2^{8-1} - 1 = 127$ (same as FP32!)

- Normal exponent range: stored values 1 to 254 → actual exponents -126 to 127

- Range (normals): $2^{-126}$ to $2^{127} \approx 1.18 \times 10^{-38}$ to $3.4 \times 10^{38}$

- Mantissa precision: 7 bits (vs 10 bits in FP16, vs 23 bits in FP32)

- Key advantage: Same dynamic range as FP32, easy to truncate FP32 → BF16

- Trade-off: Less precision than FP16, but wider range

FP8 (E4M3):

- 8-bit floating point format

- 1 sign bit, 4 exponent bits, 3 mantissa bits (E4M3)

- Bias: $2^{4-1} - 1 = 7$

- Normal exponent range: stored values 1 to 14 → actual exponents -6 to 7

- Range (normals): $2^{-6}$ to $2^{7} = 0.015625$ to $128$

- Maximum representable value: 448 (with special encoding)

- Mantissa precision: 3 bits

- Note: There’s also E5M2 variant with different trade-offs

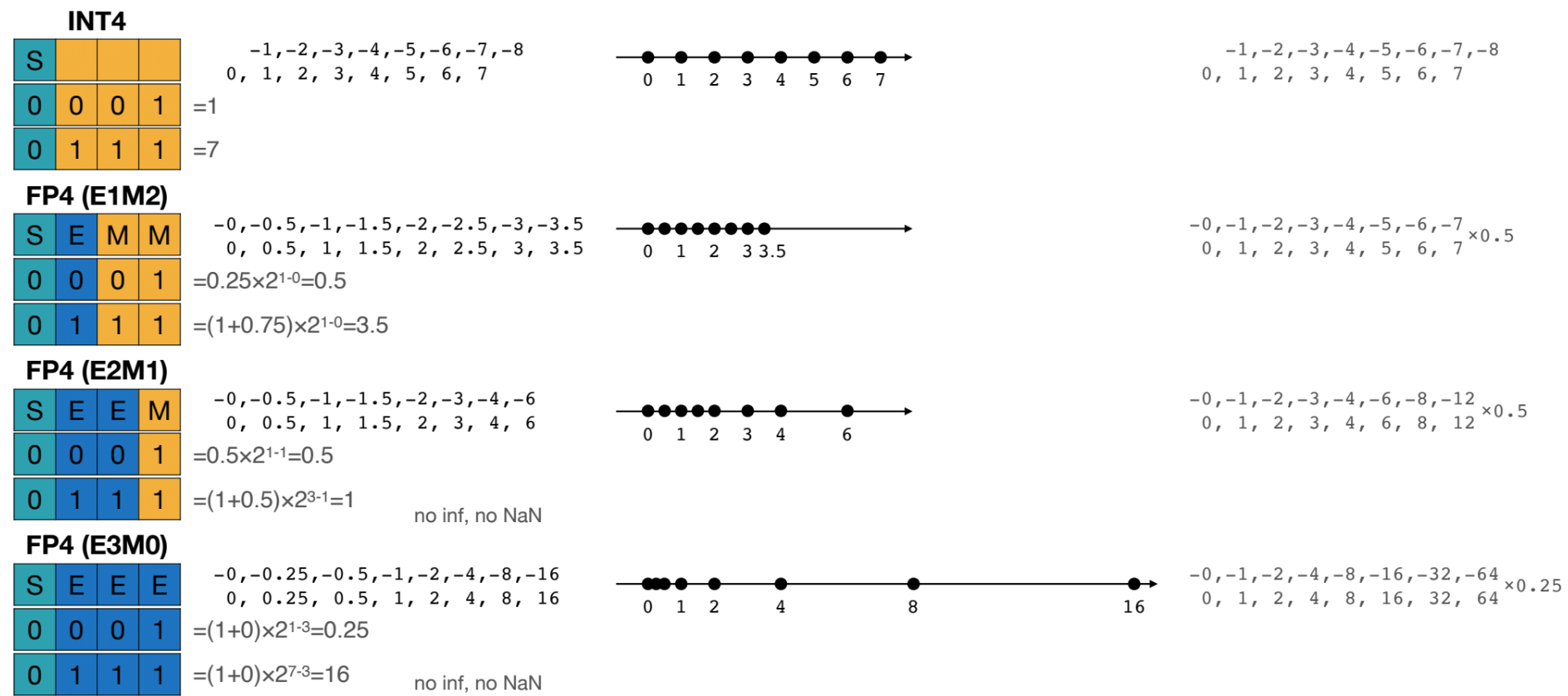

FP4:

- 4-bit floating point format (not standardized, multiple variants exist)

- 1 sign bit, 2 exponent bits, 1 mantissa bit (E2M1)

- Example configuration: bias = 1

- Very limited precision and range, only samples 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6.

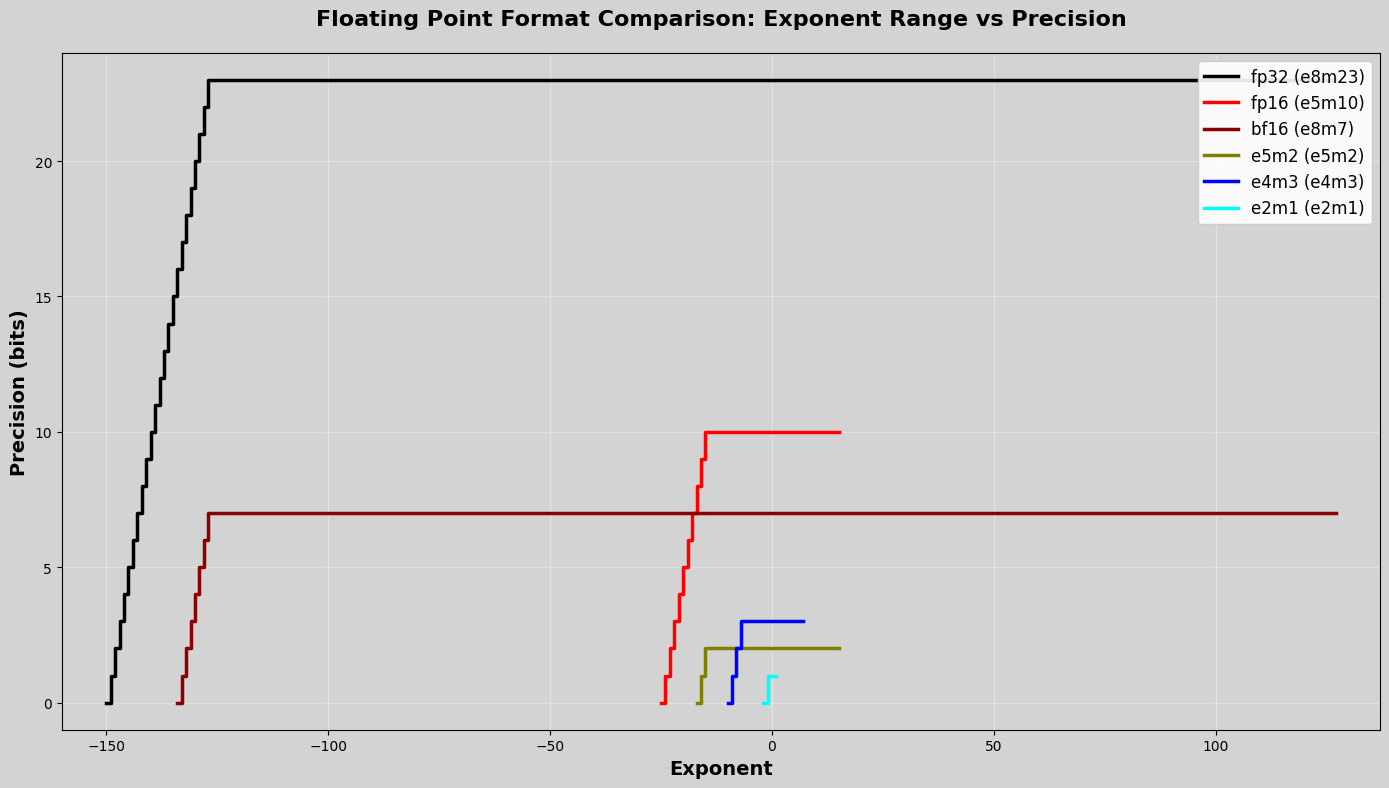

Comparison of various FP formats:

Questions?

- why IEEE FP is such format? how does it relates to FP arithmetic circuit design?

- new number format, BF16, FP8, FP8, MX4, etc? and implementation in tensor core?

FP Quirks

Routing is the culprit!

Non-associativity

In FP the order of additions matters:

- $(A + B) + C$ is not always the same as $A + (B + C)$

- Rounding to a finite number of samples is the cause (more on this later)

Things that can change the order of operations:

- Different HW: different dot-product instruction sizes

- Same HW: different compiler optimizations, use of atomics, work-queue based implementations

FP “Swamping” occurs when addition of two different magnitudes results in a sum that’s just the larger magnitude

Example with E5M2:

- $32 + 3.5 = 32$

- $1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 1.11_2 \times 2^1 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 0.000111_2 \times 2^5 = 1.0001112 \times 2^5 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5$

- last step: round the result mantissa to 2 bits (in this case loses precision) to get $1.00_2 \times 2^5$

Example with E5M2:

- Decimal: $32 + 3.5 + 4$

- Binary E5M2: $1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 1.11_2 \times 2^1 + 1.00_2 \times 2^2$

Case 1: $(32 + 3.5) + 4 = 32$

- $32 + 3.5 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 0.000111_2 \times 2^5 = 1.000111_2 \times 2^5 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 = 32$

- $32 + 4 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 1.00_2 \times 2^2 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 0.001_2 \times 2^5 = 1.001 \times 2^5 = 1.00 \times 2^5 = 32$

Case 2: $32 + (3.5 + 4) = 40$

- $3.5 + 4 = 1.11_2 \times 2^1 + 1.00_2 \times 2^2 = 0.111_2 \times 2^2 + 1.00_2 \times 2^2 = 1.111_2 \times 2^2 = 1.00_2 \times 2^3 = 8$

- $32 + 8 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 1.00_2 \times 2^3 = 1.00_2 \times 2^5 + 0.01_2 \times 2^5 = 1.01_2 \times 2^5 = 40$

FMA?

Performs $a * b + c$ in a single instruction

- Defined by IEEE 754, implemented by most modern chips (GPUs, CPUs)

- Product $a * b$ required to be kept in full precision (i.e. no rounding prior to addition)

In most cases FMA is more accurate than FMUL, FADD pair

But can lead to results that are surprising at first

- Classical example by Kahan: $x * x - y * y$ may not be 0 even if $x = y$

- Occurs when $x * x$ product requires more bits than available in format (we round)

- FMA implementation:

temp = y * y// Rounding will happenFMA(x, x, -temp)// No rounding of $x * x$

- FMUL, FADD implementation:

- rounding for both $x * x$ and $y * y$

Compiler optimizations affect how much FMA is used

- Compilers usually provide flags to control this

Questions?

How do you write a kernel to use small number format? FP8, FP4?

Reference

[1] Paulius Mickevicius, Numerics and AI: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ua2NhlenIKo

[2] Song Han, EfficientML.ai, Lecture 5: Quantization: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/qc2s9opsa2mnqfithvwz1/Lec05-Quantization-I.pdf